See the notice for upcoming dates that Rickwood Field will be closed.

Self-guided Tour

Rickwood Field was the passionate pursuit of a young Birmingham, Alabama industrialist, Rick Woodward. While still in his 20s, Woodward bought controlling interest in the city’s professional baseball team, the Coal Barons. He then sought help from the legendary Connie Mack in designing “The Finest Minor League Ballpark Ever” in this booming iron-and-steel town, the fastest-growing city in the nation at that time. Woodward’s passion was contagious.

Fueled by fervent publicity, many major businesses in Birmingham were closed for business in honor of the park’s opening day, August 18, 1910 (see historical marker 1). The crowd that day numbered 12,000, as people packed in to see the new concrete and steel ballpark, only the fifth to be constructed in the United States, and the first in the South.

Over the years, this diamond dazzled with play by some of the greatest players in baseball history. The 1910s brought standing-room-only crowds and future Hall of Famers like Ty Cobb, Christy Mathewson, Honus “The Flying Dutchman” Wagner, and Birmingham’s home team sensation Burleigh Grimes, the last legal spitball pitcher in the Big Leagues.

Beginning in 1920, in an enterprising arrangement with Woodward, the newly formed Birmingham Black Barons were also drawing overflow crowds to Rickwood Field. Alternating weekends with the Barons, the Black Barons provided a thrilling pastime for the thousands who came to watch players such as all-time Negro National League home run record holder George “Mule” Suttles and Leroy “Satchel” Paige star pitcher, who won more games for the Black Barons than for any other professional team.

Throughout those glorious early years, record-breaking crowds overflowed Rickwood’s stands. For everyone who walked through the gates, the experience was nothing short of magic. They experienced the innocence, the wonder, and the romance of baseball–the way baseball was meant to be, captivated by over 180 Hall of Famers appearing in games at Rickwood and joined by abundant inspiring Hall of Fame managers and coaches.

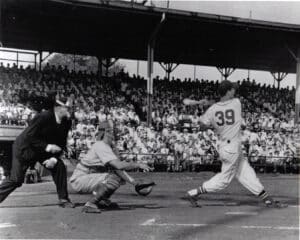

Restoration projects are continually being done in and around the park. All restorations and renovations are being done to replicate the way the ballpark looked in 1948, the year most consider the heyday of the ballpark. During that year, the Barons won the Southern Association playoffs and the Dixie Series and the Black Barons won the Negro American League pennant and appeared in the final Negro League World Series.

The park is open for self-guided tours Monday-Friday from 8:30 a.m. – 4 p.m. except holidays. Visitors can also schedule a guided tour of the ballpark by contacting the Friends of Rickwood at 205-922-3725. Also, check out Rickwood.com for more park information.

1. Main Entranceway.

This is essentially the way the corner of 2nd Avenue West and 12th Street West has looked since 1928 when the current two-story building, with Spanish Mission influences, was constructed during the first major renovation at the ballpark. The upper floor of the building was utilized for offices while the main level housed the ticket booths and turnstiles. Notice the colored tilework, barrel roof tiles, applied face gargoyles and floral shield. In 2018/9 the new sidewalks and antique-style streetlights were installed along 12th Street West, restoring the 1940’s streetscape. The Rickwood legacy brick memorial is installed at the entrance where hundreds of thousands of fans have crossed the threshold of this grand lady over the years.

2. Tickets Please!

The six original ticket booths here have seen all manner of guests pass through, from visiting dignitaries and sports legends to captains of industry. The crowds that have been entertained here over the years do not just include sports spectators but also include music lovers, circus goers, church ladies, wrestling fans and all other manner of visitors to the many events that Rickwood has hosted. In 1948, Rickwood set its attendance record when 445,926 fans saw games just in the regular season.

3. Breezeway Photographs.

When the Barons started their hall of fame in the 1940s, it was customary for pictures of the inductees to be featured on this wall. The Friends of Rickwood have added Black Baron greats. This is the primary concession area at Rickwood Field and includes the main restroom facilities featuring tiled wall urinals. Older maps of the stadium indicate this space labeled as the “privilege man” area, where patrons could socialize out of the sunlight to discuss the exciting plays of the day’s game.

4. Championship Pennant Mural

A stroll along 2nd Avenue West brings the viewer to the mural of Birmingham Barons and Black Barons Championship pennants on the northern stadium wall.

5. Left Field Bleachers and Glennon Gardens

Due to dwindling crowds in the post-television age as well as mounting maintenance problems, the deteriorating wooden left field bleachers, originally located past the covered seats, were removed sometime in the 1970s. Also gone are “Glennon Gardens,” the overflow seating area in front of the current left field wall and named for the popular Birmingham Barons skipper of the championship season of 1958.

6. Batting Building.

After Rickwood Field became the first home of the UAB baseball team in the 1970s, the UAB Harry “The Hat” Walker Batting Building was constructed with the iconic Bull Durham Tobacco sign on its south side. A tornado badly damaged the building and its use was discontinued. In 2014 Alagasco salvaged period materials from the demolition of the Birmingham Southern Railroad freight depot downtown and donated them for use in reconstructing the noteworthy batting building.

7. Drop-In Scoreboard

The original scoreboard was installed in 1928 as a part of the renovation that added this and other signature features of the park. When the Friends of Rickwood were organized in 1993, one of the very first objectives was to reestablish the park’s classic look by returning the 1948-era classic drop-in style you see today, replacing the out-of-character electric version raised in 1981. This striking icon recalls the feel of the ballpark from its origin and is both highly recognizable and a great photo opportunity for our guests. Major league ballclub listings on the scoreboard allowed staff to post scores of other ongoing games during play.

8. The Outfield Fence

Where is it now? The “original” outfield fence was constructed of wood. The left field foul pole was approximately 470’ from home while the right field foul pole was approximately 335 feet. The fences jutted out meeting at a right-angle making centerfield over 500 feet away. During the 1928 renovations, a 10-foot concrete wall was constructed out beyond the scoreboard and all the outfield signs. The only problem was it was too far away for anyone to hit a home run over it. Therefore, management yielded to marketing realities and built the wooden fence that you see now much closer in.

Where is it now? The “original” outfield fence was constructed of wood. The left field foul pole was approximately 470’ from home while the right field foul pole was approximately 335 feet. The fences jutted out meeting at a right-angle making centerfield over 500 feet away. During the 1928 renovations, a 10-foot concrete wall was constructed out beyond the scoreboard and all the outfield signs. The only problem was it was too far away for anyone to hit a home run over it. Therefore, management yielded to marketing realities and built the wooden fence that you see now much closer in.

Many old-timers say the longest home run ever hit at Rickwood was in 1948 when Walt Dropo’s mighty 467-foot blast cleared the wooden scoreboard and struck the concrete barrier halfway up. If you walk out between the current fence and one-time wall behind the scoreboard to inspect it, you can see the X marking the spot to this day. However, some people think the longest blast was hit by Reggie Jackson. On April 22, 1967, with the Birmingham A’s trailing the Knoxville Smokies, 6-3, Reggie Jackson stepped to the plate in the bottom of the ninth with two outs, bases loaded facing a 2-2 count, the future Mr. October crushed a grand slam over Rickwood’s 390-foot right-center-field fence to win the game, 7–6. Spectators recalled that the ball was still rising as it sailed out of the ballpark.

9. Current Press Box

Rickwood veterans will tell you that the original press box held a maximum of four people and was always on the roof. However, when HBO filmed “Soul of the Game” here in 1995, they emulated Washington D.C.’s Griffith Stadium which included a vintage press box exactly like this.

10. The Gazebo Press Box

You are looking at the Fullerton Gazebo, an exact replica of the original 1910 press box that adorned Rickwood Field from the very beginning. This replica was built in 1998 as a tribute to the Friends of Rickwood Field’s first executive director, Chris Fullerton of Richmond, Virginia. Prior to his untimely death, Chris often remarked that without this press box, Rickwood “appeared to be a church without a steeple.”

11. The Light Towers

Obviously, the light towers are one of the most distinctive architectural elements of Rickwood Field, contributing tremendously to the park’s antique feel. All five light towers atop the roof were erected in 1936, while the city was climbing out of the Great Depression, making Rickwood one of the first minor league ballparks to host night games. These 75-foot-high cantilevered structures represent state-of-the-art technology for the 1930s and remain virtually intact from their original mounting.

12. Rickwood’s Roof

Notice the roof that extends all the way around right field and out along the third base line. The original 1910 drawings show the grandstand roof ending at the original dugouts. In 1924, the area between the right field bleachers and the grandstand was completed with additional seats and covering. The roof and seating between the left field bleachers and grandstand were finalized in 1927. The distinctive continuation of the roof curving around the right field foul pole was installed as a part of the major renovation costing $125,000, almost twice the original construction cost.

13. Outfield Signboards

Check out all the antique outfield signs. When Warner Bros. filmed the movie “Cobb” here in 1994 starring Tommy Lee Jones, they set their artisans to work designing period outfield signs to replicate major league ballparks of the twenties. Other long-term Birmingham businesses are currently being urged to have their advertising message done in the vintage style to enhance the overall Rickwood experience and support this living piece of Birmingham history.

14. Home (and Visitor) Dugouts

Renovations to the field in 1950, including The Dugout Restaurant and 5 additional rows of box seats, meant relocating the dugouts from behind the batter’s box farther down the baselines and sunk into the field, presumably to improve line of sight for more guests. Lacking an installed drainage system, the field’s playing surface is what is called a “turtle-back field” with an unusually steep curving angle to help water drain. Due to this steepness, visitors in the dugouts have a bunker-like view of the field and have a hard time seeing beyond the infield.

15. Pitcher's Mound

From this mound, the greatest names in baseball have performed: Christy Mathewson, Grover Cleveland Alexander, Satchel Paige, Burleigh Grimes, Rollie Fingers and of course, Dizzy Dean and Ray Caldwell. In what is generally considered the most epic game ever played at Rickwood Field, an aging alcoholic – former Major Leaguer named Ray Caldwell – outdueled Dizzy Dean in 1931 to win the Dixie Series championship for Birmingham over the Houston Buffaloes.

16. First Baseline

This is the spot of perhaps one of the most romantic events that ever happened at Rickwood. During the 1950 season, Barons first baseman Norm Zauchin chased a foul ball over to the wall so hard that his momentum tumbled him into the lap of a young lady sitting in the first row of the box seats. Later, he got the usher to introduce them and the pair was married, two years later. Follow the ramp and pass out onto the concourse separating the box seats from the grandstand. Observe the park from left to right: Notice the covered right field bleachers that wrap quirkily out and around right field. Rickwood Field took Pittsburgh’s former Forbes Field as its big league model, and the similarity is striking. Probably the most distinctive change here in the grandstand since its “Golden Age” is the absence of overhead electric window fans, installed for game-watchers comfort in the hot Alabama summer and fall in the 1940s and 50s, and the wooden box seats and wooden row seats purchased and moved here in 1964 from the former Polo Grounds, home of the New York Giants. (Old timers can still recall the “NY” emblems in wrought iron at the end of the grandstand rows. These seats finally decayed and were removed in the early ‘70s)

This is the spot of perhaps one of the most romantic events that ever happened at Rickwood. During the 1950 season, Barons first baseman Norm Zauchin chased a foul ball over to the wall so hard that his momentum tumbled him into the lap of a young lady sitting in the first row of the box seats. Later, he got the usher to introduce them and the pair was married, two years later. Follow the ramp and pass out onto the concourse separating the box seats from the grandstand. Observe the park from left to right: Notice the covered right field bleachers that wrap quirkily out and around right field. Rickwood Field took Pittsburgh’s former Forbes Field as its big league model, and the similarity is striking. Probably the most distinctive change here in the grandstand since its “Golden Age” is the absence of overhead electric window fans, installed for game-watchers comfort in the hot Alabama summer and fall in the 1940s and 50s, and the wooden box seats and wooden row seats purchased and moved here in 1964 from the former Polo Grounds, home of the New York Giants. (Old timers can still recall the “NY” emblems in wrought iron at the end of the grandstand rows. These seats finally decayed and were removed in the early ‘70s)

17. The Arrow Shirt Sign

It’s gone now, but one of Birmingham’s most prominent examples of Jim Crow-ism were the reserved bleachers that once stood directly behind this sign board. Whenever the Birmingham Barons played in this park before 1963, Black patrons of the game were required to sit out in the elements blazing sun beyond the right field wall. However, the Negro American League also played here and, due to the number of future Hall of Famers they brought here (Jackie Robinson, Josh Gibson, Satchel Paige, Willie Mays, et. al.), one would have to conclude they had far superior teams. In a small measure of justice, white fans who wanted to see the Black Barons play would sit in the “Negro bleachers” during the Negro League games played here.

18. Museum and Conference Facility.

Originally constructed in 1950 as The Dugout Restaurant, this building served as a concession area complete with a beer garden. Allegedly, the only place you could get a beer on Sunday in Birmingham at one time. Later, the building was converted into a conference room for use by the Birmingham Schools Athletic Department. The Friends of Rickwood have begun the transformation of this area into a museum that will highlight the teams and players that have graced the field over the years.

That concludes your tour. Thank you for your interest in America’s Oldest Ballpark.